Westworld, and “The Bicameral Mind”

Welcome to TV Minus the TV, a column full of thoughts about TV shows watched on laptops published on the internet for you to read on your phone.

O, What a world of unseen visions and heard silences, this insubstantial country of the mind! What ineffable essences, these touchless rememberings and unshowable reveries! And the privacy of it all! A secret theater of speechless monologue and prevenient counsel, an invisible mansion of all moods, musings, and mysteries, an infinite resort of disappointments and discoveries. A whole kingdom where each of us reigns reclusively alone, questioning what we will, commanding what we can. A hidden hermitage where we may study out the troubled book of what we have done and yet may do. An introcosm that is more myself than anything I can find in a mirror. This consciousness that is myself of selves, that is everything, and yet nothing at all–what is it?

And where did it come from?

And why?

Remind you of anything?

That was the first paragraph of The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind – also known as “the book referenced in the third episode of Westworld.”

Though author Julian Jaynes is discussing the nature of consciousness, he very well could be describing the experiences of visitors upon finding themselves in an Old West facsimile freed of all social obligations and outside impositions. Robert Ford, the creator of the theme park, repeatedly stresses that people’s true motivation in going there is not the specific storylines (and certainly not the debauchery or violence!) but rather the experience of a whole world, one they can slowly examine, where they might discover some detail previously unnoticed or invisible to all others. The Man in Black, the enigmatic figure pursuing the true nature of the park, questions all around him while nevertheless asserting his power to lead and command. William, on his first visit to Westworld, is told by his abrasive companion Logan that the park will “answer the question of who you really are.”

Not one of these characters are describing a theme park.

They’re describing consciousness…

Thematically, there is no way to engage with or understand Westworld without considering consciousness. The problem of consciousness – and I do mean problem – sits at the heart of the show’s ‘maze’ of layered conflicts and mysteries. With each character and storyline, the creators are inviting us to join them in their examination of some of the most fundamental questions human beings can ask; like, for instance, why are we conscious? What are the causes of our actions? Or the inspirations of our thoughts? Why are some of us more capable of good and others of evil?

However, to fully take part in this meaningful conversation with the show, it’s important to understand where it is coming from first; what thoughts and sources have informed its perspective.

By happy chance, in mentioning The Bicameral Mind directly (and rather explicitly), Westworld provides us an entry-point…

In that early, expository episode, Ford and his associate Bernard are in the midst of a problem with the behavior of their “hosts,” the robots that populate Westworld and interact with the guests. Following a software update written by Ford, several of the hosts have deviated – violently – from their prescribed behaviors. More concerning to Bernard, though, is the way these malfunctioning hosts all seemed to have been conversing with someone named ‘Arnold’ – whom only they could hear.

Ford is then obligated to explain that Arnold, his partner in founding the park, built the artificial intelligence of the original hosts using a model “based on a theory of consciousness called the bicameral mind.”

Just as Jaynes claims primitive humanity experienced their decision-making faculties as the voices of the gods, Arnold theorized that so too would robots follow their programming were it experienced as a divine command.

But let’s slow down here for a moment to consider the original claim Arnold’s theory is based on…

Julian Jaynes, a professor of psychology at Princeton who published this theory in 1976 and died in 1997, claimed that as recently as three thousand years ago, mankind was not conscious in the way we understand it. Instead of the process of thought familiar to us, in which we weigh evidence, envision potential outcomes, and act accordingly, Jaynes postulated that civilizations like the Egyptians and the Mycenaeans were composed entirely of individuals whose mental faculties responsible for judgment and choice were inaccessible except when they manifested themselves as auditory hallucinations that were thought to be the voices of the gods.

The individual then acted upon these admonitions and urgings, not because they deemed it the most sound course of action, but immediately, thoughtlessly, as if it were the only possible course of action; a puppet of their personal gods:

If one belonged to a bicameral culture, where the voices were recognized as at the utmost top of the hierarchy, taught you as gods, kings, majesties that owned you, head, heart, and foot, the omniscient, omnipotent voices that could not be categorized as beneath you, how obedient to them the bicameral man!

This is, certainly, hard to accept without any sort of evidence, and Jaynes does an admirable job providing as much as possible, though he frequently expresses his frustration that time has obliterated so much of human achievement from the period in question.

His central source thus becomes The Iliad; specifically, the way the gods in it interact with mortals.

As he puts it:

The characters of the Iliad do not sit down and think out what to do. They have no conscious minds such as we say we have, and certainly no introspections. When Agamemnon, king of men, robs Achilles of his mistress, it is a god that grasps Achilles by his yellow hair and warns him not to strike Agamemnon. It is a god who then rises out of the grey sea and consoles him. […] It is one god who makes Achilles promise not to go into battle, another who urges him to go, and another who then clothes him in a golden fire reaching up to heaven and screams through his throat across the bloodied trench at the Trojans, rousing in them ungovernable panic. In fact, the gods take the place of consciousness.

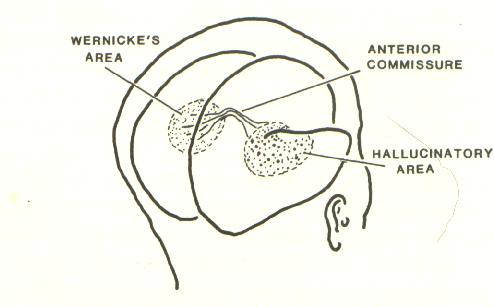

Jaynes called this theory the “bicameral mind,” meaning two-chambered, because he noticed that all of our language faculties are located in the left hemisphere of the brain. Damage to the area can be catastrophic for someone’s ability to speak and write, but damage to the corresponding area on the right hemisphere can seem harmless. Why this inconsistency, he wondered, when almost all our other functions are redundantly located in both hemispheres? It is demonstrable, however, that this right hemisphere area is capable of perception and deliberation; it just lacks the ability to express itself. The right hemisphere, he concludes, must have once been the seat of reasoning, operating independently of the left hemisphere. It then expressed its judgments to the left hemisphere through language that was experienced as a disembodied voice.

Now, whether or not we accept this claim – that this use of the gods is not a literary technique of Homer’s but a true depiction of how people thought at the time – Arnold clearly admired it when he first designed the Westworld hosts. Ipso facto, understanding the bicameral mind can help us better understand the baseline behavior of the hosts.

For example…

The hosts are unable to lie to the diagnostic programmers who work with them at the park, and while there are satisfactory, pragmatic reasons why this would be a necessary component to their code, it is actually a by-product of a bicameral organization of the mind. Deception is a complex mental process that requires the ability to consider oneself and distinguish between one’s external presentation and one’s internal beliefs. Because any bicamerally organized mind lacks the power to consider the self in this way (as it lacks the power to choose what to focus its reasoning faculties on), deception is impossible.

In other words, in the hosts’ purely bicameral mind, “thoughts” are simply a combination of sensory reaction and the “divine” commands of Arnold. There is no room for a sense of self, and thus no room for deception.

Fortunately, neither the book nor show are interested in dwelling in the purely bicameral mind…

Much more compelling is the way consciousness begins to emerge through its breakdown:

Chaos darkened the holy brightnesses of the unconscious world. Hierarchies crumpled. And between the act and its divine source came the shadow, the pause that profaned, the dreadful loosening that made the gods unhappy, recriminatory, jealous. Until, finally, the screening off of their tyranny was effected by the invention on the basis of language of an analog space with an analog ‘I’. The careful elaborate structures of the bicameral mind had been shaken into consciousness.

Why the bicameral paradigm began to give way in the second millennium BCE Jaynes struggles to explain, with the historical record as spotty as it is and all. He ventures some hypotheses relating to population growth, trade routes, and mass migration. And he emphasizes the glacial pace of these changes; this “breakdown” took millennia to complete.

Regardless, if it did exist in the first place, we can confidently say the bicameral paradigm gave way then. Carvings of kings standing speaking to their gods# gave way to distraught rulers kneeling before empty thrones#. The mind was changing; people were becoming conscious.

And the gods were disappearing.

Meanwhile, in Westworld (/Westworld), Bernard succinctly summarizes the hosts’ own, hyper-accelerated evolution when speaking to Theresa in the final scenes of the seventh episode:

Out of repetition comes variation. And after countless cycles of repetition, these hosts, they were varying. They were on the verge of some kind of change…

By forcing the hosts to follow the same routine day after, year after year, unplanned changes began to build up in their behavior, and in their very manner of thinking.

Ford’s “reveries” update – which insisted on giving the hosts tiny ‘learned’ behaviors based on prior personal experience – only compounded this problem, as allowing hosts to recollect and draw knowledge from the past in turn helped them locate various experiences in a timeline; severely altering their relationship to time by spatializing it. The spatialization of time is of critical importance to the development of consciousness because it allows us to think in terms of cause and effect.

Or, more applicably, of “after” and “therefore.”

Like one emerging from hypnosis (which Jaynes calls a modern vestige of the bicameral mind) Dolores’ father, Peter, finds himself suddenly able to discern the anachronisms in the park left by careless guests:

But while he struggles to place himself and these images into a coherent timeline, his bicameral voice reasserts itself in an attempt to make sense of this new information and provide guidance.

Unfortunately, much like the Greeks used poetry to convey the truths embedded deep in The Iliad, Peter Abernathy’s personal god can only express his new understanding of his world by quoting Romeo and Juliet to Dolores – “These violent delights have violent ends” (Act 2, Scene 6) – setting off a host of reactions in her, all of which conform to what Jaynes tells us to expect during a period of what he called “bicameral collapse.”

As her developing analog self allows her to imagine the potential paths she could follow, Dolores begins to hallucinate another version of herself who often takes actions she would never consider. At the orgy in Pariah she consults an oracle (and is clearly shaken by its prophecies), following Jaynes’ observation that “as the slow withdrawing tide of divine voices and presences strands more and more of each population on the sands of subjective uncertainties, the variety of technique by which man attempts to make contact with his lost ocean of authority becomes extended.”

Speaking to Bernard in “Dissonance Theory,” Dolores boldly confesses:

I feel spaces opening up inside of me, like a building with rooms I’ve never explored.

Creating a gulf between perception and the voice rendering judgment, Dolores has become, in Jaynes’ description, “the wedge between god and man that results in consciousness.”

Submitted To Sci-Fi, Television, TV Minus the TV

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Danny Sullivan.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.