Reclaiming and Returning: The Politics of Domain Hacking

In the background of www.la, a site offering registration of the top-level domain .la, is a panoramic snapshot of Los Angeles.

It hits every note of the city’s postcard-caliber iconography: a sequence of palm trees, a russet coastal sunset, the jewel-lit monoliths of the downtown skyline:

“.LA is the domain that says ‘local to LA’,” the site’s About section exclaims.

To be sure, plenty of Los Angeles businesses have registered .la domains, leveraging its their regional associations and broad availability (relative to traditional suffixes like .com). Nevertheless, the site’s casual confidence obscures .la’s real identity: the official domain suffix of Laos.

While an unofficial emblem of Los Angeles, .la is officially assigned to the country of Laos…

Ostensibly, there’s nothing amiss here. “Domain hacking” – a term denoting the process of co-opting a regional domain in a foreign area for branding purposes – is a generally accepted practice; the likes of Instagram (instagr.am; .am for Armenia), YouTube (youtu.be; .be for Belgium), and Reddit (redd.it; .it for Italy) are exemplars.

However, beneath its slick succinctness lie geo-political power imbalances that can’t be ignored as the practice of domain hacking gains popularity.

In 1996, “.la” was introduced as the country-code top-level domain (ccTLD) of Laos. By 2007, the LA Names Corporation, which had the rights to market the domain, transferred .la to the British company CentralNic. This allowed such sites as GoDaddy and the aforementioned www.la to sell .la registration. (The Laotian government likely collects a portion of the fees, but the percentage isn’t publicly disclosed.)

Seeking exposure and profit, CentralNic began to market the domain to Los Angeles businesses, anticipating high revenue from a major American metropolis.

“[LA Names and CentralNic] wanted to make a lot of money and register a lot of domains,” said Thomas Johnson, CEO of DotVN, the official registrar of .vn, Vietnam’s ccTLD:

“Their take on it was, ‘How can we get people to register? Most people don’t know Laos, but people do know Los Angeles, so let’s go that direction.'”

As the .la domain became more heavily associated with Los Angeles, Laos, a developing country with limited technological access, was pushed to the fringes.

“The Laotian government is disappointed in the way it was managed and the way it was marketed,” Johnson added. “No doubt, there was a lot of registration, but it in no way helped Laos and its citizens.”

It’s help that’s certainly needed. Laos remains one of Southeast Asia’s poorest nations; a landlocked country, it lacks territorial access to the ocean and relies on neighboring countries like Vietnam and Thailand for trade. Worse, landlocked developing countries pay significantly more in transport costs and face more obstacles in exportation than coastal countries. Between trade-corroded funds and limited access to resources, the country’s infrastructure – from roads to telecommunications connections – suffers.

Johnson noted that during a recent visit to Laos, “they would turn off their internet at night. [Developed countries] have servers and data centers, security – they had a PC 386, which is archaic.”

Despite this, Laos has seen recent economic growth, and local internet use is rapidly expanding. According to the World Bank, the percentage of Laotians using the internet has jumped from approximately 1.2% to over 14% in the last eight years.

In light of this, in 2011, the Laotian and Vietnamese governments announced an agreement to “reclaim and relaunch” .la as a Laotian emblem.

As part of the agreement, Vietnam would host .la while training the staff of the Laotian registry, Laotian Internet Network Information Center (LANIC), to host the registry platform full-time. Though LANIC has made the transition, the effort to reclaim the domain is ongoing. CentralNic continues to market the domain to Los Angeles, though Johnson said its contract with the Laotian government expires this year, noting Laos is “in the process of looking at a more favorable registrar to assist them with representing .la properly.” It’s currently considering Dot VN. #.

“With the ability to register more domains for their citizens and have their citizens use it to educate themselves and advance themselves, perhaps they’ll be able to break the chains of poverty,” Johnson said.

The once-coveted “.io” domain presents a similarly fraught case…

The ccTLD for the British Indian Ocean Territory (also known as the Chagos Islands), .io became the object of affection for countless American tech startups around 2011, their founders relishing its resemblance to the computational term “input/output” (abbreviated I/O, IO, or io).

The islands’ history, however, has caused a network of startups to reevaluate their purchases…

In 1965, amidst the heightened tensions of the Cold War, the United Kingdom purchased the islands from Mauritius, a nearby self-governing colony, to lease the island Diego Garcia to the United States as a military base. The countries signed a 50-year contract, with the option of extension, and began to forcibly, and secretly, evict the existing civilian population – the Chagossians – with no compensation. The Chagossian people, who’ve settled on the islands of Mauritius, Seychelles, and in in the British town of Crawley, have struggled with barriers to language, education, and employment. Meanwhile, their desire to live on the islands is steadfast; a 2015 government survey found that 98% of a pool of 844 Chagossians wanted to return, and U.K. nonprofits have been campaigning for the right to return for years.

Alongside their efforts, however, .io remains a sobering reminder of the Chagossians’ displacement.

A private company called Internet Computer Bureau (ICB) serves as the .io registrar, likely giving the British government, which owns the Chagos Islands, a percentage (also publicly undisclosed) of the registration fees#, but “for us,” said Stefan Donnelly, Committee Chair of the U.K. Support Chagos Association, “[.io] feels like a symbol of everything that’s happened to Chagossians in the past – their heritage, their culture. What should have been theirs has been taken from them.”

Donnelly also said the organization’s efforts to learn how the .io registration fee is distributed have been lost in the abyss of red tape:

“It’s something we tried to find out. It seems to be quite a lot of work, but I can definitely say the Chagossian people don’t get any of [the funding].”

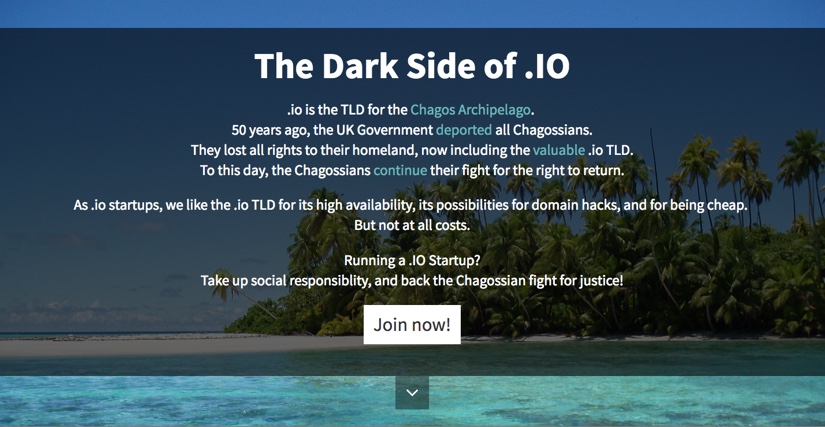

While most startups were likely unaware of the .io issue when they registered their respective domains, many learned of it through a story on Gigaom in 2014 (which the U.K. later challenged). In response, two such companies, seats.io and bigboards.io, founded The Dark Side of .io, an initiative encouraging businesses with .io domains to match their registration and renewal fees with donations to Chagos support nonprofits.

Donnelly said the money has funded such activities as right-to-return campaigning, cultural celebrations, and English lessons.

Domain hacking remains a popular marketing strategy, meaning it will continue to present unique, if opaque and convoluted, nexuses of countries.

Libya, for example, requires registrants of its .ly ccTLD to comply with Libyan sharia law, and in 2010 it controversially seized writer Violet Blue’s sex-positive URL shortener vb.ly for promoting “pornography and adult material” – leaving many to question the status and management of other .ly sites (namely, bit.ly).

In the process, though, it looks to be the responsibility of both governments and enterprises alike in considering who their agreements will truly affect.

Laotian internet cafe image courtesy of Flickr/Jon Rawlinson

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Julianne Tveten.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.