The Parable of Pokemon Go

Every few hours, the train station a block from my Chicago apartment switches control. New colors go up, and new groups are no longer welcome.

Blue, red, blue, red.

This isn’t about gangs, though. This is about teams, the cousins of gangs, which are much more upfront about their arbitrary divides…

Pokemon Go teams, to be specific.

Nintendo has been pushing moderation and interaction in its mobile games for years now. In Animal Crossing: New Leaf, villagers will comment that the player looks tired and should think about taking a break. In The Legend of Zelda: A Link Between Worlds, saving the game after playing for a half hour or so will prompt a message encouraging you to put the game down for a while. At times, it may feel like your overbearing mom has found a way to write you virtual notes, but these are the actions of a company that actually cares about its players.

In fact, almost every handheld game and system manual Nintendo has released recommends that the player stops playing for fifteen minutes to every hour played…

Pokemon specifically has been encouraging IRL interaction since Red and Blue’s original release all the way back in 1996. The dual-version rollout strategy (Red had Pokemon that Blue didn’t have, and vice-versa) acted as an inherent incentive to connect with one’s fellow Pokemon players. Your Machoke wouldn’t evolve to its full potential on your game alone#; it needed to be traded. Oh, you want to complete your Pokedex, the ostensible goal of the games? Better make some friends.

As technology advanced, the opportunities (and push) to play Pokemon together evolved as well. Contests, mini-games, chat rooms, and multi-battles became widely available to anyone with an internet connection; all strategically fueled by an algorithm that rewards you with stronger Pokemon that grow quicker the more you play with other people. And with the release of Pokemon Go, the most technologically universal of all the Pokemon multiplayer universalities, more people are able to play together than ever before.

Having the latest handheld Nintendo gadget might be hard for some people to justify – especially since they release a New 3DS or a 3DS XL or a 2DS every nine months or so – but, in 2016, everyone has a smartphone:

Pokemon is a franchise whose beauty lies in its vague quest narrative, more like a parable in its simplicity. Everyone’s experience is inherently similar, yet still intrinsically unique; a phenomenon only highlighted by the near-ubiquitousness of Pokemon Go. We near the train turf war, for example, are so close to the lake that everyone has a Dewgong or a Cloyster accompanying their Pidgeot and variously (and often vulgarly) nicknamed Raticates; it’s part of our shared experience as Lakeview Chicagoans.

Maybe it’s because the game is so upfront about the lack of substantial differences between teams or the lack of tangible consequences for controlling the gyms, but this game supposedly based on lone scavenging and head-to-head competition has only served to foster and build-up our community rather than set it against each other. By removing the impetus of completion – the ultimate goal of the Championship, or Elite Four, or any other sort of end-game – Pokemon Go has embraced the kind of ambling enjoyment of an Animal Crossing-style game: you play it for the fun of playing it.

— for the people you meet along the way…

Putting its game design where its mouth is, Pokemon Go has found a way to encourage its users to build real community. Dropping “lures” at particular landmarks – say, a park – attracts wild Pokemon and, with them, those seeking Pokemon. And while these gatherings of like-minded trainers assemble out of shared interest and mutual beneficence, many gamers have already anecdotally shared stories of making friends, exchanging numbers, and going on dates with people they’ve met – yes – outside.

The other day, I talked to a group of genuinely cute girls genuinely interested in learning the location of a Tauros (outside of a donut shop), and even arranged a “Pokemon Go date” on Tinder in which we plan to explore the city together. I can definitively say I’ve never been stopped on the street by one pretty girl before, let alone a group of them. Now it’s like a city-wide scavenger hunt and everyone’s working together for no goal other the joy of playing.

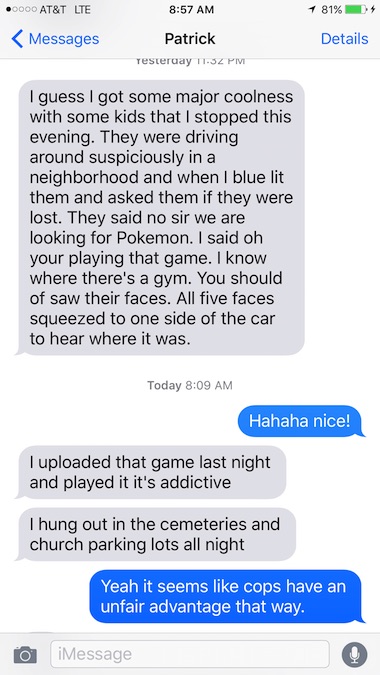

The game’s accessibility and flexibility has allowed players to interact with the other members of their communities, who were there all along, by using the now mutually-understood language of Pokemon:

Sure people have been robbed, caught cheating, stumbled upon dead bodies, and found themselves embroiled in a philosophical battle with enterprising, progressive trainers who insist on controlling their Westboro Baptist Church gym with a Clefairy named “LOVEISLOVE”#, but this is more attributable to people actually venturing beyond their apartment caves into the daylight than to Pokemon Go. We as humans crave an excuse to be social creatures, and if catching smaller, virtual creatures is an icebreaker, so be it.

Because, above all else, this game has given us an excuse for kindness and connection that costs us nothing.

Hospitals have been supplying lures so more and more Pokemon show up for bedridden kids. Strangers on the streets now point out Pokemon to each other regardless of race, age, or appearance. Overweight and socially-anxious people are leaving the nonjudgmental safety of their homes for the first time in years.

It took eight years, but Michelle Obama finally figured out a way to get our generation in shape. #PokemonGO #PokemonFitness

— Ken Crocker (@IdeallyDumb) July 7, 2016

Still, if Pokemon Go really is the thing that ultimately allows for teens and police officers to find common ground, for us to replace our suspicion with relation, then that’s both beautiful and kind of sad.

The passivity of Pokemon Go is a psychological boon for community-building because it pre-built the social infrastructure hard part and let us do all the easy, satisfying work. We don’t need to figure out the best bars, meetups, or museums; we don’t need to think of those hard, first words of introduction. The logistics of gathering are no longer up to us. Anything that laziness or procrastination or fear of awkwardness could undermine has been taken out of our hands, leaving a social system whose only requirements are an ability to move and an interest in sacrificing a few cool points for some cartoon critters.

So, if this fad is ever going to truly be more than just one magical month of one sunny summer where we all roamed the streets with the shared purpose of capturing a bit of augmented reality, then it’s up to us – the users and individual members of these communities we’ve recently realized we’re a part of.

Sure Niantic Labs will release new content and expand to new countries (and eventually change how the game monetizes its items if it’s not recouping costs), but the power to turn this surge in community-building into a springboard to realized local community development is literally right at the fingertips of the 15 million humans who have downloaded the game already.

Could Pokemon Go be a way to organize parents against gun violence? Could we hold demonstrations, protests, cross-cultural discussions through the color-, religion-, and politic-blind lens of Pokemon? I like to think so. Though that’s probably because I’m Team Mystic and love analysis.

Speaking of, it looks like I need to go on a walk to the train station…

Submitted To Mobile Gaming, Pokémon

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Jacob Oller.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.