The Madding, Ignoble Strife of Crowdsourced Journalism

Proponents of crowdsourced news call the Arab Spring breathing proof that citizen journalism is both powerful and functional. The democratic liberalization of the web, they argue, has democratically liberalized the states (and people) that now have access to it.

Composed of mostly locals, the “citizen journalists” of the Arab Spring used sites like WordPress and YouTube to blog content relevant to those living in their village or country, or who shared their language, thus making the content hyperlocal.

In turn, their coverage was incredibly effective in producing change…

However, much like the ubiquitous stereotype of the citizen journalist as the young, English-speaking traveler of means who enthusiastically documents protests via social media (definitely Twitter, probably Facebook too), U.S. companies have capitalized on the idea that a Western tool saved the Middle East and North Africa. The success of crowdsourced journalism has jumpstarted the trend of creating content platforms instead of news outlets, like web traffic heavyweights Slant News, CNN’s iReport, Periscope, and Medium.

Industry leaders have argued that the crowdsourced model will “save” journalism from becoming an irrelevant industry, claiming most articles people consume online (like, say, this BuzzFeed listicle entitled “22 Secret Thoughts Israelis Have About Gaza”) aren’t real journalism anyway. Shane Snow, the CCO of Contently, asserts, “The fact is: Most of what we read in magazines or watch on television or browse on the Internet is not journalism. It’s information, education, entertainment. But not Journalism.” Therefore, getting more untrained ‘journalists’ to create content, then, wouldn’t sacrifice the current quality (or lack thereof) of digital media.

To believe this caricature is to believe citizen journalism began the moment Apple put a camera on our phones and made cellular data use ubiquitous…

When media executives get excited about citizen and crowdsourced journalism (particularly in the context of foreign reporting), what they’re usually really getting at is acquiring scandalous footage of war-torn states, or of innocent people impacted by horrifying violence; frequently at the expense of the practical, necessary advantages of having an established, objective, and accountable journalistic establishment.

Fresco News, a crowdsourced journalism startup, is one of the most rapidly growly news sites on the market: It raised $1.2 million in seed investments last fall alone.

Its app turns users into citizen journalists, giving them news assignments like footage of the South by Southwest arts and tech festival, or photos of major weather events, and allowing them to submit photos and videos they’ve taken on the scene. From there, content partners (which currently include about 11 21st Century Fox affiliates#) can pay users for their footage — $20 per photo, and $50 per video.

The company’s model is appealing, for obvious reasons, when covering international breaking news.

The Ukraine/Russia conflict, Israel/Palestine violence, Fukushima, the Arab Spring — it’s now all fair game for more “complete” coverage…

“One of the upsides is the ability to procure content from anywhere and everywhere,” Sean McCready, Fresco’s content director, says.

“I remember one shift I had, and it was a submission through Twitter actually, someone sending us photos from a Yemen [factory], of the aftermath of a Saudi airstrike.

They were photos of mangled corpses. I’ve never seen even less-graphic photos of an airstrike like that.”

Submissions like that are both boon and albatross, though.

On Twitter, outside the purview of Fresco’s localized verification software, it becomes more difficult to confirm the photos were taken where users say they were (one of the reasons, McCready says, Fresco doesn’t solicit photos from the site).

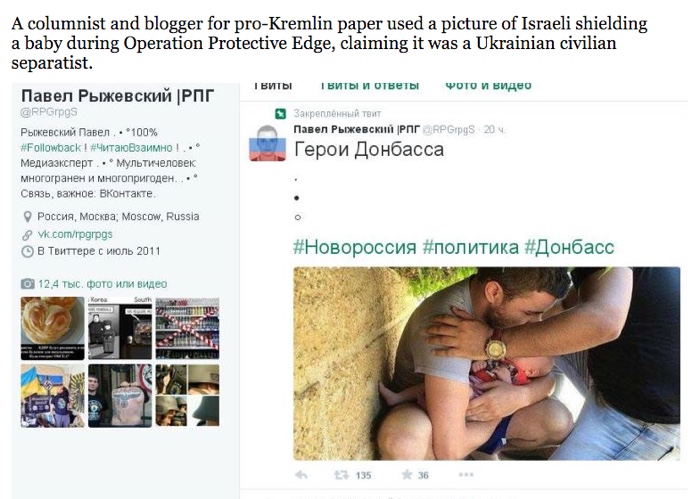

As this election season has proven, you can’t trust everything you see on the Internet, and when there are no journalistic standards, no set of agreed-upon rules to play by, people stop playing fair…

Just look to falsified images coming out of Beirut or Jerusalem. As recently as the March bombing in Brussels, videos claiming to show the airport instead depicted years-old attacks on airports in Moscow and Minsk.

Moreover, even when the images are real, there are consequences for both viewers and editors to consider.

A 2014 study of 116 journalists shows that user-generated content of violent and graphic war images leads to post-traumatic stress disorder in the journalists and editors responsible for determining which images to publish.

That’s not to say the media doesn’t have a responsibility to disseminate brutal and sometimes undesirable images – the infamous images of Aylan Kurdi, the drowned three-year-old Syrian refugee, are some of the most important and valuable documentation of human suffering# – but the line between journalistic ethic and financial incentive has begun to blur to the point of disillusion.

“How can we fault the media for showing us images of what they know will get our attention?,” Dean Obeidallah asked in a CNN op-ed after two journalists were murdered by gunfire on-camera last August. “After all, the media is a business. The media outlets are simply serving us up what we crave.”

“If there’s a problem,” he defends, “it lies with us, not them.”

That editorial decision — whether or not to publish violent, graphic and scarring content — is one which essentially every editor must grapple with. It’s also one of the reasons the institution of journalism exists, as opposed to being left to the devices of consumers, or citizens, themselves.

Social media is capable of giving a voice to people living in violence, who are terrified and angry, and who are using personal blogs as a megaphone for the society in which they live. Regardless, when it comes to the co-option of their shocking and gruesome images of violence, it seems that Western sympathies will always trump political, moral, or journalistic blowback.

For thee, who mindful of th’ unhonour’d Dead

Dost in these lines their artless tale relate;

If chance, by lonely contemplation led,

Some kindred spirit shall inquire thy fate,

– Thomas Gray

, “Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard”Submitted To Facebook, Foreign Affairs, Twitter

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Morgan Baskin.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.