Twitter Is a Nightmare of Social Anxiety, or: Why I Couldn’t Play Animal Crossing as a Child

I like Twitter a lot. Not only does it provide me with a convenient outlet for the uninterrupted stream of pearls perpetually spilling forth from my beautiful brain#, but Twitter is an awe-inspiring social tool. Complete strangers can share stories, common rabble can gain unprecedented insight into the mental processes of our graven celebrity idols, and a fellow from Dallas can even accuse me of “sexual confusion” in response to a tweet voicing my support of Wendy Davis. Twitter makes it easy to keep in touch with friends who’ve moved far away, it’s a great place to bat around ideas with colleagues, and it’s connected me to true, flesh-and-bone-dimension friends. I’d even go so far as to say I love Twitter. I love you, Twitter.

But you’re fucking killing me.

It’s not the trolls. Quite the opposite, actually. I welcome trolls; I invite them, so that the heat of their rage may keep me toasty and comfortable during the unforgiving deep freeze of the winter months. The energy expended by those anthropomorphic Cheeto-piles shall provide me with eternal youth, much like the South American mummy woman from that one episode of Buffy the Vampire Slayer. So it’s not the trolls, and it’s not due to fogeyish fear-of-technology type reasons, and it’s not because it eats up my monthly allotment of data like a horde of locusts.

Twitter has slowly but thoroughly tenderized my brain because there’s always more of it.

To the chronically anxious individual, the endless stream of new #content is crippling, overwhelming.

Bear with me: I enjoyed video games during my boyhood years#, and as a dyed-in-the-wool Nintendo faithful, I once received a GameCube for Christmas. Upon hearing the news, a school-friend was eager to lend me a game that he spoke of with hushed awe, as if it was a religious artifact or dog-eared copy of Penthouse. It was a different sort of game, he assured me. “It’s a role-playing game, but not built around fighting or journeys or the usual video game stuff. You buy a house and get a job and make friends with people around town,” he explained. No sooner than I had realized that that sounds a lot like doing life every day, than he shoved the case into my hands. The bright, friendly cover art read “Welcome to Animal Crossing, Population: Growing.”

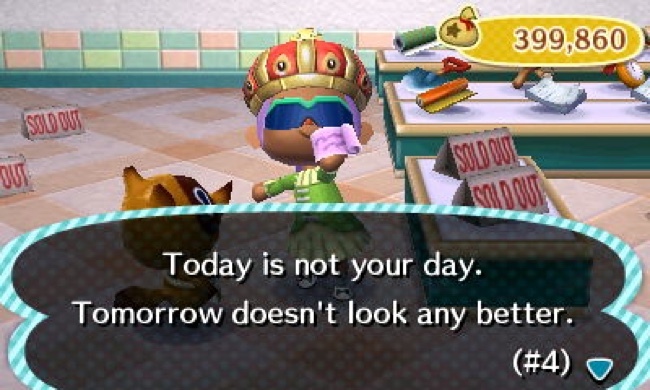

I didn’t know enough then, but if I could go back, I would’ve defaced it with a warning to others: “Welcome to Hell Crossing, Population: Maddening.”

One element in specific made this seemingly innocuous Animal Crossing game such a serious threat to my psychological health: Its internal clock.

The game basically plays like a cutesy version of the Sims; it simulates life, steering a main character through the wonders of home ownership, interpersonal relationships, butterfly catching, etc. etc. Through some dark technological magicks, however, the designers created something I had never encountered before. For the first time in my life, here was a situation in which the world of the game exists outside of the extent of your character’s interaction with it.

It’s a sort of narcissistic perspective to take, but such was the nature of console video games at the time. Shut off the console and the game ceases to be until you’re ready to engage with it again. It horrified me that when I revisited the game after first playing for a couple hours the day before, the characters recognized my absence. I hadn’t been around lately! They missed me! What had I been up to? Little things around town had changed, too. Fruits and leaves laid in different locations, characters had moved around, buildings now served different purposes. Essentially, I had missed part of the game. Things had happened within the city limits of Animal Crossing and despite my status as the owner of the game, I was not there for them. This haunted me. At night, I couldn’t get myself to sleep knowing that Mr. Resetti was out there, doing stuff, getting mad about resetting without me. Rattled to my core, I returned this cursed game to its owner after a couple days. I told him it wasn’t for me, but didn’t expound on why.

Clearly, this is the thinking of a madman. But that’s the thing about social anxiety — it’s impervious to logic and reason.

In the anxious mind, the manageable and innocuous stresses of everyday life cast ghastly shadows, turning into looming terrors. Every failure, even failures so mundane and minor that they barely have the significance to qualify as such, feels like the one to end them all.

It’s mostly the terrible flashes of perspective. When I forget to promptly send an e-mail to an editor, I fear that I’ve demonstrated to the intended recipient that I am neither dependable nor professional. This, in turn, precludes me from getting future work with that outlet, and effectively derails the very course of my life on a large enough scale to topple the whole structure. Social anxiety fools you into believing that in the grand scheme of things, your every slip-up spells certain doom.

Twitter has a nasty way of exacerbating these perilous ways of thinking. Social success and failure are so easily measured in fav’s and RT’s, and the never-ending scramble of professional networking creates the feeling that you’re wasting time if you’re inactive. But really, that’s not what makes me so anxious when it comes to Twitter.

It’s that damned internal clock.

Twitter is a modern-day salon where the brightest intellectual minds of my generation can trade dick jokes, but the problem is that it never stops. I can’t turn it off. I can put down my phone and close my laptop, but the world still exists no matter how tight we shut our eyes.# When I’ve been away from the social-networking platform for long enough, I’m struck with the sensation that all my friends are hanging out without me. But that’s only because they are.

Again, it’s a crazy-person thing to take people’s tweeting so personally, but that doesn’t stop the nagging suspicion in the back of my brain that whatever stretch of Twitter that goes unseen contains hilarious jokes to which I’m not privy or links to fascinating material I might not otherwise find. You can call it FOMO if you like, but I want to be clear: It is the fear of missing out, but not on something as banal as a laugh from a joke-tweet or a favorite from an esteemed colleague.

It’s the fear that I’m missing out on life.

Submitted To GameCube, Social Media, Twitter

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Charles Bramesco.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.