Appreciation for Loss, and the Pokémon Nuzlocke Run

After twenty years of collecting and battling Pokémon, a generation (myself included) has grown up playing the games. However, as you might imagine, the way we enjoy the games has shifted as we mature. The wild-eyed, simplistic discovery has been replaced.

But with what?

In a 2014 interview with Wired, Junichi Masuda (a founding member of Pokémon developer Game Freak and director of the games Ruby and Sapphire) and Shigeru Ohmori (his hand-picked successor) discussed Pokémon’s multi-generational appeal:

When we developed Red and Blue we weren’t explicitly targeting children. If you look at the animation, for instance, that was meant to appeal to kids with cute designs and so on. But if you look at the game and that design, even from Red and Blue it was intended to be a game that adults could also enjoy.”

As he later put it: “Children and adults both like playing soccer – children might like it at first because the ball is round and colorful but adults put far more thought into it”.

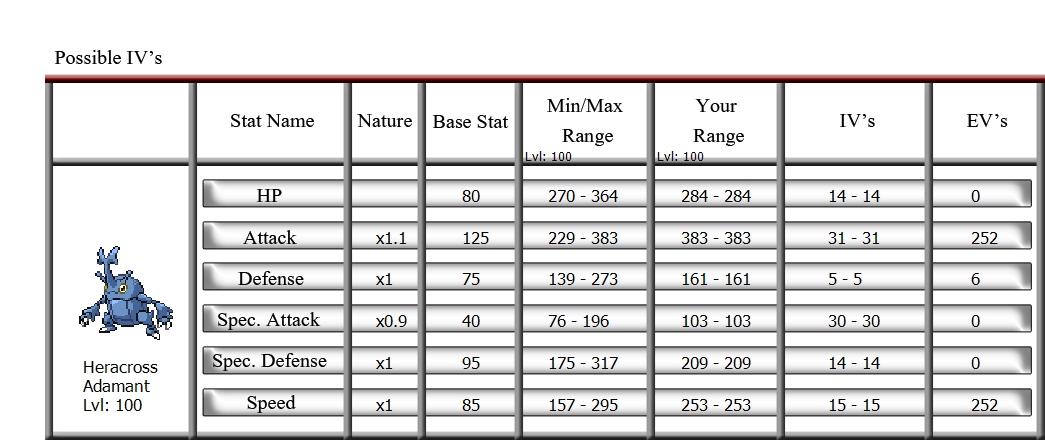

Some enterprising Pokémon enthusiasts have put extreme amounts of thought into the games themselves, diving deep into the game’s code to find out what makes certain Pikachus better than others. The result: a surefire, spreadsheet-driven way to breed the best of the best – primo fighting machines with the highest raw numbers (attack, defense, etc.) the game will allow. That means lots of monotonous grinding back and forth, digging for the right combination of Individual Values (random game-assigned starting stats), and training against the right kinds of opponents to gain the right Effort Values (stat bonuses given based on Pokémon defeated).

That’s one side of the hardcore Pokémon experience; cold, clinical number-crunching.

However, these Individual and Effort Values are kept superficially hidden from the game’s audience, mostly due to the ideology of its creators. Ohmori once compared this way of playing Pokémon to choosing a pet dog based on a chart tracking dog-based data – totally soulless#.

I mean, just look at this shit…

Pokémon may not be as faithful of companions as dogs, but you can actually develop a connection with your team. In the same vein as a well-loved Tamagotchi or Sim, you grow attached to seeing the same digital faces over and over again. You’re responsible for them – you’re their God, their caretaker – not just making sure they get food or have a roof over their head, but that they survive the outcomes of the multitude of battles the games put you through.

Which brings us to the other side of the grown-up Pokémon player’s experience…

The Nuzlocke Challenge.

The Nuzlocke challenge comes from a comic created in the winter of 2010 by an artist at UC Santa Cruz (likely staying anonymous due to his early use of racial and homophobic slurs) documenting the imposition of two rules on himself to make his unchallenging, repetitive games of Pokémon more interesting:

1. You can only catch the first Pokémon encountered in each new area.

2. If a Pokémon faints (a regularly curable condition), it is considered dead and must be released.

The comic found fans on 4chan (remember those slurs?) and, thanks to the artist’s combination of the Pokémon Seedot# (and subsequently Nuzleaf#), and the TV show Lost’s John Locke# as a recurring gag character, the “Nuzlocke” Challenge was born.

The Nuzlocke Run ramps the difficulty past the rather simplistic rock-paper-scissors tactics the games use to pit fire against water, not by changing this core mechanic, but by removing the safety net of the ubiquitous and socialistic Pokémon Centers that restore your team to full health and revive fallen friends at no cost.#

As the original website says, “there is no victory without loss.”

Untimely critical hits and a lack of control over your companions mean that loss is almost inevitable, and with permanent loss – even self-moderated permanent loss – the stakes become infinitely higher. In this, the player finds the difference between the satisfaction of godlike power when you feel powerless (as a child) and that of a challenge when you feel too powerful (playing a game centered around catching and training cartoon beasts when you’re in your twenties).

Maturity, it turns out, comes from setting up and subsequently following rules and boundaries.

It’s not about limiting your enjoyment by limiting creative freedom, but through the added freedom of being a grown gamer; your knowledge and expertise allows you to thrive in more harsh (and rewarding) conditions – like Pokémon death.

From this difficulty springs forth new avenues for forming narratives, especially encouraged by the popular ancillary rule of mandatory nicknames for all Pokémon.

For example, naming your Pokémon after your friends, loved ones, or acquaintances can help dust off the imagination and build bonds with your virtual fighters. The losses you feel are then tied to their names. It’s not just a Geodude, it’s your friend Eric. He’s tough as hell, but dammit it if he doesn’t miss more often than not. That’s character.

And that’s the Nuzlocke Challenge phenomenon: everyone has a story.

Pokémon that never would’ve seen the light of day become trainers’ valued teammates. Temporary injuries become stress-inducing, knowing any knockout would mean goodbye. Battles are closely won, heroes forged when victory seemed impossible, and martyrs created and memorialized.

Like a good Dungeons and Dragons campaign, the story makes the struggle worth it…

This search for meaning, the imposition of narrative where none exists, returns one to the days of pure imagination – one of the many reasons why so many of these playthroughs are mythologized by webcomics, comment threads, and message boards. People love telling their stories, and each one is different; different teams, different struggles, different losses and overcome obstacles within the same basic framework.

Growing up means our entertainment consumption must inherently grow with us. Imagination and creativity could easily stagnate with the overwhelming selection and ubiquity of TV, movies, video games, and webseries. But with something as simple as the Nuzlocke Run and a rainy day, it’s possible to both recapture Pokémon’s thrill without scoffing at a children’s game or pushing the numbers until they burst, but with ever-evolving storytelling fantasy.

Submitted To Nintendo, Pokémon

Like what you read? Share it.

(That helps us.)

Love what you read? Patronize Jacob Oller.

That helps us and the writer.

What is Patronizing? Learn more here.